At the end of September, a few stories popped up around the 30th anniversary of Nirvana’s Nevermind. I was surprised, not because it had been 30 years—that bit made sense—but more because I just hadn’t clocked it as an event upcoming. Had completely put out of my mind that markers and anniversaries mean stuff, especially in things like music and art. I’m not mad at that reality. Time spans are as good a thing as any to review what’s happened in history and how the intervening years have unfolded for both those involved and those who held the event as important.

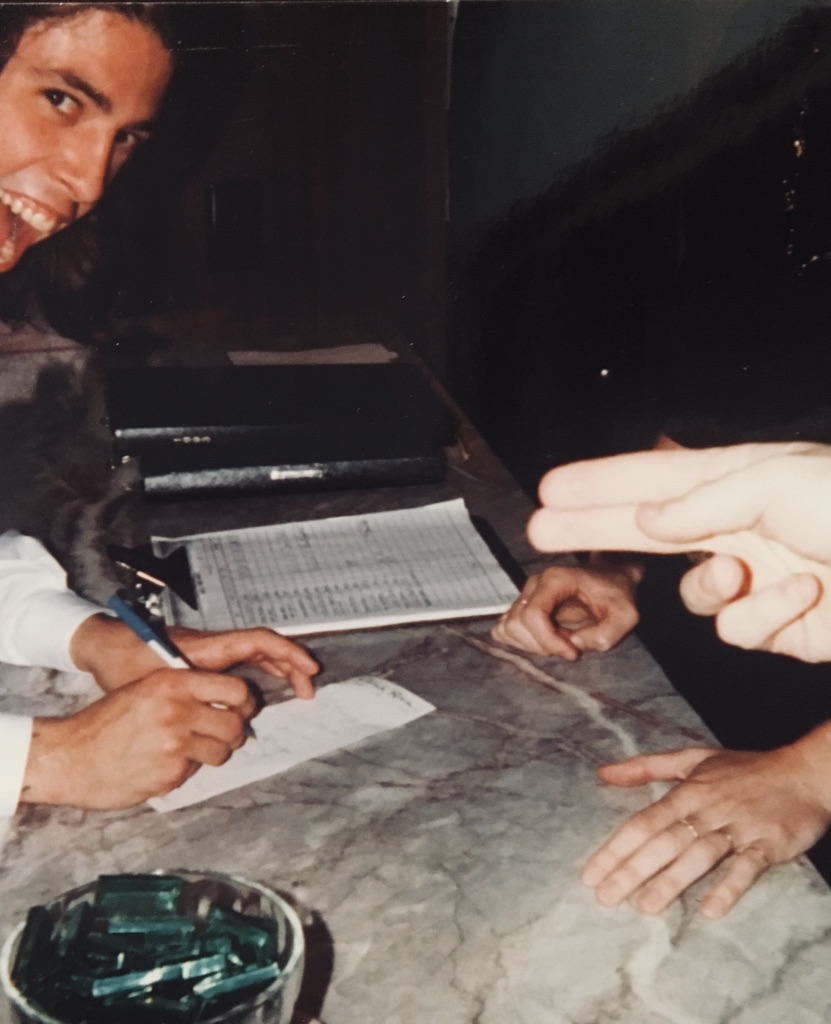

On the 20th anniversary of said release, I wrote a piece in the Guardian about the album, band, and its subsequent impact and while at first I was nervous to revisit that period in my life, the experience ended up being cathartic. But even then I felt I’d lived a few lives since hearing, loving, and standing in the full-force wind of Nirvana’s music and the movement it hurricaned inside of. The adage forest-from-trees comes to mind. I’d be lying if I didn’t say I knew that span of time and scene was electric, fractured, complicated, effin’ amazing. All those feels also had to do with my understanding that I was actually doing what I loved: writing about and documenting rock’n’roll music. Ever since teenagehood, consuming Creem and HIt Parader magazines, listening to shaggy British bands who wore their jeans really tight, I’d wanted that job. And, once getting it, I buckled in and went for the ride, eyes open, trying to hold onto my pen. Losing its grip on the regular while watching my reporter’s notebook fly off the ride and I’d think, Damn, hope I can remember all this. There was an adjacency to the magic that was potent and much looser than it seems to be today. Publicists were different back then. Not as much security and vetting of stories. You actually really could set up an interview and step into the room without reams of resistance and the stern parameters around stories that exist in this century. But because there were no guardrails inside the industry some very crappy things were happening (I’m looking at you sexism, bullying, racism, general shittiness).

And also because it was such a wild ride, when I did get off, knees all shaky, equilibrium upside down and sideways, my instinct was to step away. Very far away. I ended up going into NYC public school classrooms and teaching writing workshops because I actually wanted to be with nine-year-olds who acted mostly age-appropriate. One thing I forgot to do was pay attention to why I felt so keenly that I had to step away from music altogether. Or at least investigate what lay beneath. Look at. Wonder why I ran screaming from the building. Obviously, that’s a big heaping bit of hyperbole, but in my mind, I see myself actually running toward the revolving door out of the Elektra Records offices at full speed with my hair on fire. In reality, I simply didn’t renew my contract as head of video promotion, then packed up a cardboard box and took a car service home once my last day was over. It was September 1994. The April before Kurt Cobain had died from suicide. I found out Kurt was gone as I sat in my office with Huey Lewis (remember him and the News?) and his manager as they grilled me on why VH1 was not rotating the video from their newest album. I remember thinking Wait. What? How? Why am I sitting here talking to these guys? Oh, shit, I have to keep it together. I watched their mouths move and that’s about all I remember. I didn’t run screaming anywhere at that point. I didn’t even reach for a bottle of anything, even though I knew where one was.

In Rage Becomes Her, author Soraya Chemaly talks about how often women are expected to show the world a calm outward face while guys gnash teeth and rage around without anyone shushing them. I kid you not, there were wails, gnashing, and high-emotion from adjoining offices, yet I finished the meeting. Reality check: I’d been shoving store-for-later emotions down deep for decades. (Side note: Chemaly also brings up some very stark stats around women leaving the industry where they’ve been unheard, unseen, and harrassed within five years of incidents happening or situations building. They usually end up in jobs far far away from the industry they’ve left.) When I did leave that job for good and the business for real, it felt like an amazing weight off. But one I never talked about. Just, you know, moved on. Actually left a lot of the friends I’d had at the time behind. Got married, which was really the ultimate hide for real. Since then I’ve reacquainted with most of those friends and unacquainted with the marriage. But only fairly recently have I looked into the closet with the various (metaphorical) rubber maid bins holding eras of my life and thought to fully unpack them.

I know there are a bunch of false bottoms in those bins. I open one, a hole at the bottom gives view into the next. I understand on a very basic level that I’ve lived all these moments. I recognize how my fiction is play-doh-ing them into stories (or maybe Mr. Potatohead-ing), and how this really is my life. And I do love it. I actually love it more now for the distance. The other night I was talking to friends who I’ve known for well over a decade and they wondered how it was some of these stories around brushes with music&people were just coming up now in conversation. How had we never talked about it before? Such a good question. This grab-bag of things from what I sometimes think of as my former life are actually moments from this actual, real, yes-I-remember-well time. And you know, I’m not in any way sad about that. It may just be when I’m told to remember because it’s been X-amount of years and that time was really important and let’s remember why that I balk, but that may be because sometimes I respond like a nine-year-old.